- Home

- Liz Harfull

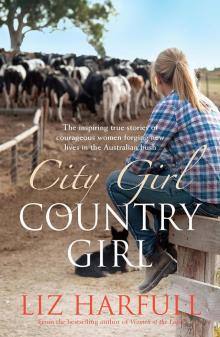

City Girl, Country Girl

City Girl, Country Girl Read online

Liz Harfull is passionate about telling the stories of regional Australia, its people, communities, history and traditions.

Liz grew up on a small farm near Mount Gambier, which has been in the family since the 1860s. She became an award-winning rural journalist and communicator and director of a leading national public relations agency.

In 2006 Liz walked away from corporate life to write books. Her leap of faith was rewarded two years later with The Blue Ribbon Cookbook, which captured the stories and traditions of South Australian country shows and show cooks and became a surprise bestseller. It won a Gourmand World Cookbook Award in Paris. Since then she has written two national bestsellers, Women of the Land and The Australian Blue Ribbon Cookbook, as well as Almost an Island: The Story of Robe, about her favourite seaside town on the windswept Limestone Coast.

Today Liz lives in the Adelaide Hills, juggling a busy writing career with travelling around Australia to visit the places and meet the people that inspire her writing.

www.lizharfull.com

lizharfullauthor

@LizHarfull

First published in 2016

Copyright © Liz Harfull 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 9781742379814

eISBN 9781952533488

Internal design by Simon Paterson, Bookhouse

Front cover photograph: Nigel Parsons

Cover design: Christabella Designs

Typeset by Bookhouse, Australia

Dedicated to the memory of my mum, Elaine Harfull: a city girl who married a country boy and (almost) never looked back

CONTENTS

Introduction

PART I: LONG LIVES WELL LIVED

Elaine Harfull, Mil Lel, South Australia

Grace Gilmore, Eight Mile Creek, South Australia

1 The Boy in Blue

2 Life at Mil Lel

3 For the Love of Grace

4 Till Death Us Do Part

PART II: LOVE IN A FOREIGN LAND

Doris Turner and Wendy Bonini, Manjimup, Western Australia

Giuliana Vincenti, Carmel, Western Australia

5 Child of the Forest

6 The New Chums

7 The Outlaw Returns

8 Tall Timber Dancing

PART III: THE LITTLE TOWN THAT COULD

Marnie Baker, Harrow, Victoria

Sherryn Simpson, Connewirricoo, Victoria

9 The One Nun Story

10 New Life and Almost Death

11 A Beaut Bloke

12 Lessons for the Teacher

13 Connewirricoo

14 The Ripple Effect

PART IV: RESILIENT SPIRIT

Daljit Sanghera, Bookpurnong, South Australia

15 A Long Way from Home

16 Trusting Your Luck

17 To the Riverland

18 When Giving up is not an Option

PART V: HERE I AM, HERE I STAY

Annabel Tully, Sarah Durack and Wendy Tully, Quilpie, Queensland

19 Creative Cowboys

20 Grass Castle Legacies

21 The Fence of Hope

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

I’m sitting down to write the opening lines of this book a year to the day since my mum died. She is constantly in my thoughts, not just because I miss her terribly, but because she was the inspiration for this collection of stories about women who have come from very different places to make a new life in rural Australia.

Mum was a city girl. She spent most of her life in Melbourne until one eventful evening when she met a country boy on leave from the Royal Australian Air Force. It was wartime and society had been turned on its head, throwing together people who might otherwise never have crossed paths at all. Less than a year after the war ended, my parents married in a celebration kept discreet because clothes and food were still rationed. Mum had to save coupons for her dress and the reception was a modest repast of cold meat, savouries and trifle. After an adventurous honeymoon in the wilds of Gippsland, they took up residence in a dark, limestone farmhouse at Mil Lel near Mount Gambier, with no electricity and practically no plumbing.

It was the beginning of a very different life for an independent woman who enjoyed a respectable job as a bookkeeper in the city, a dashing wardrobe of the latest fashion, and the social whirl of going out to dances with her sister and friends several nights a week. While the farm was not that isolated, Mum found herself an arduous journey and a whole world away from Melbourne. Over the coming years she learnt to milk cows, stook hay and drive a tractor, playing an active part on the farm while raising four children. In between, she also learnt to match her mother-in-law’s skills at making Dad’s favourite cakes and puddings, hand-stitched all the babies’ clothes, transformed the old farmhouse into a bright, modern family home, and volunteered to do her bit for a host of local community organisations.

In many ways, my mum’s story is not unique, and nor are those of the other women featured in this book. Thousands of women have faced similar challenges after leaving behind the city, or another country. A whole new generation are experiencing them now. If reality television shows that help farmers find wives and the sale of rural romance novels are any indication, many more women are dreaming of following in their footsteps and falling in love with a tall, rugged country bloke wearing RM Williams boots and a wide-brimmed Akubra hat.

But behind the stylised, romantic visions that people have of the Australian bush can lie a very different truth. Loneliness and isolation, the lack of essential services and facilities often taken for granted in the city, and the vagaries of drought and floods challenge any woman, whether she is from the city or country bred. Then there are the long back-breaking days of hard work, with few days off, and the constant financial struggles for many farm families, coping with the ups and downs of commodity prices and the demands of fad-following city consumers.

Mum says that in the early years she would cry whenever she left Dad to visit her family back in the city, and she would cry again when she left her family to return home. I’m guessing a piece of her was always missing, no matter where she was, and I’m guessing this because that’s how I felt, too. In my early twenties I reversed the trend, married a city boy and took up an urban life 400 kilometres away. The marriage didn’t last but my city life made me appreciate the things I had taken for granted while growing up in the country.

Things like the freedom we had as children to wander the farm and the neighbourhood. Spending our days outside in fresh air and open spaces, riding our ponies to visit friends, and using our imaginations to make up our own games. Sitting in the back of an old ute, bouncing across a paddock, the wind making waves in the coat of our border collie, Boofa, struggling to contain his excitement at th

e prospect of work to be done.

Things like the closeness of the community which made it impossible to go to the post office to collect mail or to pick up something at the local farm supplies store without allowing extra time to chat about the weather and how the crops were looking, and exchange news about the family and mutual friends. Neighbours dropping in cakes and casseroles at times of tragedy and loss, practical symbols of their care and concern. The camaraderie of community celebrations and knowing almost everyone crowded into the local hall and showground. The nonchalant wave of passing drivers acknowledging even complete strangers.

And then there was the traditional country baking and preserving—tastes, smells and experiences that led me to write two books about show cooking. Afternoon tea before setting off to bring the cows in for milking, with home-baked scones and cake, often shared with neighbours who dropped in, knowing the routine. Tommy the Caltex Man, who came every month to fill up the fuel tank in a ritual that stretched back decades, always timing the run so he could share a cuppa, too. And the supper tables at community events in the hall—trestle tables groaning with ginger fluff, strawberry sponges, corned beef and mustard pickle sandwiches, and homemade sausage rolls.

On our farm there was always a menagerie of animals. The border collie waiting patiently at the back door, not bothering to even lift his head if Dad emerged wearing his town boots and hat. George the cockatoo barking like a dog whenever a vehicle pulled into the yard. The bulls roaring over the back fence when they sensed the herd of cows nearby, and the calves that slobbered over your jeans and pulled at your fingers with raspy tongues as you tried to feed them from a bucket. The cats sitting in a circle at your feet at the top of the haystack, waiting for mice to appear as you lifted each sheaf of oats. And the horses—patient Prince who taught me and my sister how to ride, gentle Rusty who thought it funny to sneak up behind my brother and blow in his ear, and Toby the rescue horse, the first horse of my very own, who waited for me to get off the school bus every day.

Life on a farm connects you to the rhythms of nature and the changing seasons. The smell of fresh-mown pasture when haymaking starts in the spring, and discovering a batch of mewling kittens hidden in the shed. The setting sun glancing off paddocks of bleached stubble after the harvest is over, and the croaking of frogs from the swamp as a summer storm approaches. The dancing clarity of an autumn night sky crammed full of stars, undimmed by intrusive streetlights. Coming in from the crisp winter chill to the comforting warmth of a wood stove and a huge pot of lamb, vegetable and barley soup simmering on the back.

These are the things my mum came to love, too, as more than sixty years of marriage passed, and she watched her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren grow. Mum knew that I was planning to tell her story, and I thought deeply about the best way to approach it. In the end, I decided to treat her the same as every other woman in the book, and tell it in the third person. Mum’s story focuses mainly on her life before I came along, but when I do make the odd appearance, I have stayed true to her overwhelming preference and used my full name, Elizabeth. Mum didn’t think of her life as anything exceptional, but she was quietly proud at the idea of being part of the book. There is much more I would have asked her, but she died unexpectedly after a very short illness and the opportunity was lost.

Recognising that has made me all the more determined as a writer to do what I can to capture the lives of other women, the quiet, seemingly small lives, well lived, and so often overlooked, who make up the rich fabric of our rural communities. Women such as Annabel, Daljit, Marnie, Sherryn, Wendy, Elaine and Grace.

Liz Harfull

19 June 2015

1

THE BOY IN BLUE

Elaine Schwennesen hated the Big Dipper, its bone-rattling swoops that left your stomach back on the last rise, the ear-piercing shrieks that rose over Luna Park. She really wasn’t sure how she had been talked into going. Bushfires had caused havoc across Victoria for weeks in what was proving to be a hot, dry summer but she and her sister Reay were shivering with cold and the park was crowded with servicemen on leave who seemed a little the worse for wear. Now her best friend Maree was ‘rolling her eyes’ at one of them.

Maree had taken an instant fancy to Arthur who was out on the town with three of his mates, all flight engineers in the Royal Australian Air Force. They were camping at the Melbourne Showground on the other side of the city where the RAAF No. 1 Engineering School was based, and had come into a hotel near the Swanston Street Station for a slap-up meal to celebrate completing an engine-fitting course. Afterwards they hopped on a tram to the seaside suburb of St Kilda and its popular amusement park.

Thousands of summer holiday-makers had passed through the gaping mouth of the iconic Mr Moon gate since the park opened thirty-two years before, but it was even more popular during what seemed like a never-ending war that encouraged people to seize pleasure when they could. It was January 1944, and the conflict had been going for almost four-and-a-half years, although things were finally looking up. Just that morning the front page of The Argus was reporting Allied advances in Italy, German retreat in Russia, and the Japanese being forced back by the Australians in New Guinea.

Looking at the group of young men gathered around them, Elaine focused her attention on the handsome boy with dark blue eyes made even bluer by his RAAF uniform. He seemed sober, and in the raucous setting of Luna Park looked especially quiet and dependable. ‘You had better come along and look after us,’ she told him.

Lyall Harfull was not about to turn down the opportunity to spend more time with the tall, slim brunette. A few weeks shy of her nineteenth birthday, she was wearing a soft blue dress with flowers embroidered on the sleeve and a demure, buttoned-up collar. Later on, in the custom of the day, she would give him a photo of herself wearing that dress, signed very properly ‘To Lyall with best wishes, from Elaine’.

At the end of the night Lyall walked her to the tram, and then unbeknown to Elaine and her sister, he and his mates jumped on the back. ‘They thought we were nice girls and they wanted to see that we got home safely,’ Elaine would tell her children years later, when they asked her to relive the magical moment that lit the spark that became their family.

The next day Lyall took Elaine up into the nearby Dandenong Ranges with a party of friends for a ride on the Puffing Billy steam train. ‘It was stinking hot and he was dressed in these lovely shorts. He used to look nice in his shorts. And he sat down under this tree and ate lots of watermelon,’ Elaine said.

After watching them together, one of Lyall’s friends turned to him at the end of the day and predicted, ‘You’re going to marry that girl.’

Alma Elaine Schwennesen was born in a small private nursing home in the central Victorian goldmining town of Bendigo, where her father worked as a butcher. The year was 1925 and the month was February, but after that the facts are a little unclear. According to details registered by her father, she arrived on 27 February. According to her mother, she was born three minutes after midnight on 28 February and that is the date on which her birthday was always celebrated. In fact, Elaine didn’t even realise it was in doubt until thirty years later when she required a copy of her birth certificate to apply for a passport.

Never known by her first name, which she hated, Elaine was the first of four children born within five years to Bruce Schwennesen and Vida Marriott. Originally from Denmark, her father’s family were tailors at Talbot, a once-thriving town in the heart of the Victorian goldfields. She remembers her Grandfather Schwennesen as being a hard, cold, ‘nasty’ man, but she was deeply fond of her Grandpa Marriott, who was a staunch Methodist, went to church three times on Sundays and looked after the Sunday school. A travelling salesman for part of his life, at one stage he also owned the Federal Dairy in Bendigo and he had worked in the mines as a younger man.

When Elaine was only a few years old, her family moved to Frankston, on the southern side of Melbourne. Her father found work as a

butcher and there always seemed to be food on the table, even during the worst years of the Great Depression. Occasionally, there was a little spare money for special treats. The whole family would sometimes walk to the grocery shop on the corner and buy a large bag of honeycomb. ‘And if they were in season, we would get peaches on a hot night and come home and have them with ice-cream,’ Elaine recalled.

After living in three different rental houses in the one street, they fetched up in a place on top of a hill, opposite the railway line. It had a big garden, with a creeping vine growing over the fence and a side gate through to their landlords, the Rogerson family. Elaine had very fond memories of those years and their neighbours, particularly Mrs Rogerson. ‘She had one arm and a hook for the other and she taught me to knit. She was like a second mother to us.’

By the age of six, Elaine was good enough at knitting to make her own school jumper, navy blue with a thin light blue stripe around the bottom—a feat that staggered the man selling Griffiths tea when he came to call on his rounds one day and was invited to inspect it. She proved to be good at remembering numbers, too, after a gifted teacher at the school put her class through a daily exercise in which he would write five rows of five numbers on the blackboard, then rub them out and ask the students to write them down unaided. And she loved to dance. She and Reay were both sent to the Vesper School of Dancing, which ran lessons every Saturday in the Frankston Mechanics Hall. Elaine learnt highland and tap dancing, becoming so proficient that, at age ten, she was chosen to lead the opening number at the school’s annual revue.

Elaine was in grade four at the Frankston State School when she caught diphtheria from a boy who sat next to her in class. The disease was extremely contagious and rife in parts of Melbourne, where whole schools were shut down at that time in an attempt to stem the spread. Called in at night because she was delirious with a soaring temperature, the family doctor recognised the symptoms and sent immediately for an ambulance which carried her away to the Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital. Within days, Elaine was joined by Vida, Reay and youngest brother John, despite her mother’s attempt to disinfect the house by sealing cracks around the doors with newspaper and burning sulphur.

City Girl, Country Girl

City Girl, Country Girl