- Home

- Liz Harfull

City Girl, Country Girl Page 2

City Girl, Country Girl Read online

Page 2

The rest of the family recovered within a few weeks, but Elaine was kept at Fairfield for three months and two days. The fact that she remembers the amount of time so precisely is telling. Her experiences through the illness remained among the most distressing of her long life. Perched above the Yarra River at Fairfield, the hospital was opened in 1904 to treat patients with potentially deadly ailments such as typhoid, cholera, smallpox and poliomyelitis that killed thousands before vaccines were developed. Elaine was put upstairs in Ward 2. From there she could see another ward downstairs full of even sicker children. ‘At night time we could look down on this from the balcony where our beds were and see them wheeling the little kids that died out to the morgue. Often two and three a night, wheeled out covered in sheets.’

Elaine had never been away from home before and she missed her family terribly. Once Vida was discharged, she was only permitted to make one visit and they were not allowed to hug, or even touch. Elaine was kept behind a wire cage, with her mother standing no closer than a few metres. No doubt such draconian measures were considered necessary and the hospital may well have been applying the best practices of the day to help their patients get better and reduce the risk of infection, but it was a traumatic experience for the young girl.

If a child at the hospital was discovered to have lice or fleas, everyone in the ward was completely submerged in a phenyl bath. And if a child wet the bed, one of the nightshift nurses thought the best deterrent was to smack them hard on the bottom with an open hand. Elaine had kidney problems before the diphtheria and was unfortunate enough to have this happen more than once.

The invalid diet they had to eat was pretty terrible, too. ‘Our food came on a trolley and was usually a gluey mass by the time we got it,’ Elaine said. ‘We had tripe for lunch every day, and then rice or sago for dessert, and for tea we had milk and bread at three o’clock and then nothing else before we went to sleep. The doctor would come and swab our nose and throat every day [to check if patients were clear of infection], and we would be given two pieces of fruit after that, which was the highlight of our day.’

Elaine was not given a clean bill of health until the doctors removed her tonsils, and the swabs cleared.

She was about eleven when her father became seriously sick, too. He contracted double pneumonia and pleurisy, so the doctor suggested he should move to a drier climate and give his lungs a chance to recover. The Schwennesens settled on the tiny dairy farming community of Leitchville, not far from the River Murray, between Kerang and Echuca.

They took on a local bakery business and moved into a house with a small shop at the front, on the road leading to the railway station. Bruce baked bread at a separate premises off the main street, in an enormous Small and Shattell oven that still stands today, an historic curiosity in the centre of a new bakery. He delivered the bread by horse and cart to neighbouring areas, while Vida made the smallgoods at home. ‘Mum would cook things like cinnamon slices, Napoleon cake, lamingtons and all sorts of other cakes. She would cook these in a wood stove in our kitchen and the whole table would be covered,’ Elaine recalled.

The school at Leitchville only went as far as year seven, so to finish her education Elaine was sent to Bendigo, where she boarded with her mother’s parents, the Marriotts. During the week she attended the Bendigo Girls’ School, as it was known then. The first school of its kind in Victoria, it was set up in 1916 to teach the domestic arts to teenage girls as part of their formal secondary education. When Elaine went there in the late 1930s, it was very much about turning out the ‘perfect housewife’—someone who could keep a spotless house efficiently and economically, sew and mend clothes, and cook tasty meals for her husband and children.

As part of the curriculum, she was taught strict rules for everything from dusting and polishing to hanging clothes out to dry, and the preferred order in which to iron the components of a man’s shirt—shoulders first, then the back, then the sleeves, the front panels and finally the collar and cuffs. The campus also had its own small cottage so the students could practise their housekeeping skills. Elaine applied these lessons every day during her married life, and did her best to pass them on to her daughters, too. At least once a week, the students would plan and cook a three-course meal which was served to the general public in the school’s purpose-built dining room. Recipes more often than not came from the Presbyterian Women’s Missionary Union Cookbook, which remains a much-loved bible in many Victorian households more than a hundred years after it was first published.

Elaine seemed to enjoy her time at the school, but she was only part way through her secondary education when Grandpa Marriott died, in odd circumstances. ‘One night I tried to say goodnight to him as usual, but said “goodbye” instead, even when I tried again,’ she explained. He was late getting up the next morning so Elaine was sent to wake him. She found him dead in his bed. The discovery upset her so much that she panicked and ran down the street in her nightie to an aunt who lived nearby. After the funeral Elaine boarded with other relatives, who shared their house with her dreaded Grandpa Schwennesen and his wife.

While Elaine was finishing her education, the family moved back to Melbourne where her father bought a delicatessen at Glen Iris. Elaine worked with him for a while after returning from Bendigo, but when World War II broke out she found a job using her mathematical skills as a book-keeper for one of Melbourne’s best-known menswear businesses, Fred Hesse Pty Ltd. Named after its owner, by then the business had three stores in the city, offering both bespoke tailoring and ready-to-wear clothing marketed with the catchy slogan, ‘Be thrifty and dressy, be clothed by Fred Hesse’ (pronounced Hess-ie). During the war the company also became military tailors, making uniforms for officers.

Elaine worked in the main office, at the Elizabeth Street premises, under the steely eye of Miss Jenkins, who later also employed Reay. A formidable woman who kept a close eye on her staff, Miss Jenkins insisted on immaculate book-keeping. Elaine was given an adding machine, and she had to account for every single penny. On at least one occasion that put her in a very awkward position. ‘There were a lot of nice blokes that worked there, and I had to dob one chap in. He was part of the gang and we all used to go out together, but one day he didn’t send up the money for a military hat that he sold, and I had to report him.’

Some customers had accounts but the majority of business was cash sales. Payments would be delivered immediately to the office upstairs via a wire pulley system. Staff working at the cash desk on the sales floor would place the money into a small metal canister attached to the wire, and then send it up to the main office by pulling a cord. Elaine sometimes relieved the staff on the cash desk on the shop floor, and she was also given responsibility for carrying the day’s takings to the bank in a small case.

She enjoyed the work and the social life that went with it. Every Monday, Friday and Saturday night, a group of employees would go dancing. There were plenty of choices given it was wartime and social dances were popular with the thousands of American and Australian troops in transit through Melbourne or visiting on leave.

On Monday nights ‘the gang’ would usually head to the Earls Court Ballroom in St Kilda where their employer sponsored a variety program with singers accompanied by dance bands, broadcast live on Melbourne radio. Afterwards, they would have supper together somewhere in Acland Street. There would be more dancing on Friday night, usually at St Kilda, and then on Saturday nights the girls would ‘dress up to the nines’ and head to somewhere like the Caulfield Town Hall where there were regular cabaret balls.

Elaine was a good dancer and never short of partners. She even learnt the latest American craze, the jitterbug, with its twists and spins and tosses, that in its most exciting moments saw her flying through the air and rolling over her partner’s head. After meeting Lyall at Luna Park, Elaine didn’t go dancing quite so often. He wasn’t that keen on dancing but he loved going to the cinema so he often took her to the pictures when he coul

d get leave.

Within weeks of their meeting, Lyall was called home to work on the family farm. Labour was in short supply and his parents and only brother, Ross, weren’t coping without him. Lyall loved being in the RAAF, the camaraderie, the lifelong friendships he made, his work as an aircraft engineer, even the food and the routine. In between training in Melbourne, he was based at the flying training school at Mallala, north of Adelaide, maintaining Avro Ansons for the learner air crews, and he was just about to be promoted. But farming was considered an essential service for the war effort, so the RAAF discharged him and, reluctantly, he headed home.

Shortly afterwards Elaine paid her first visit to the farm, accompanied by her fourteen-year-old brother, John, as an unlikely chaperone. They boarded a train at Spencer Street Station and travelled as far as Hamilton in western Victoria, where they caught a bus to Mount Gambier, about 140 kilometres further on, just over the South Australian border. Now the state’s largest regional city, Mount Gambier at that time was a small country town of only a few thousand people, surrounded by farmland. Most farmers ran dairy cows, which thrived in the cool climate. A high rainfall and rich soils produced plenty of pastures, which the cows happily converted into plenty of milk.

Milking cows was part of the Harfull farm enterprise, too, along with growing oats and breeding working horses. The farm was in the rural district of Mil Lel, about eight kilometres to the north of the town, where Lyall’s grandfather took up a small parcel of land in the mid 1860s. A shipwright’s sawyer who worked in the naval dockyards at Portsmouth in England, John migrated to South Australia with his pregnant wife and their young daughter in 1853. He headed south to Mount Gambier sometime in the late 1850s, not long after the township was officially proclaimed, and set up a carrying business. Using horses and a wagon, he moved produce and supplies between local stations and ports along the coast, as far east as Portland and west as Robe.

The farm was bought with money earnt from the business and saved under the judicious eye of his wife, Marina, who also applied her skills as a midwife in between raising nine of her own children. Meanwhile, John’s expertise with a saw and adze stood him in good stead when it came to putting up post and rail fences, building a house and clearing the land, which was heavily forested with eucalypts and blackwoods, and ferns almost as tall as a man on horseback. Lyall’s father, William, who was born on the farm in 1868, loved telling the pioneering stories of those days and so did his son. Elaine soon became familiar with them, too.

Apart from meeting Lyall’s family, during that first visit Elaine also had the chance to experience something that was very much a focal point of the Harfulls’ lives. The house was always filled with music. His mother, Amy, was a gifted amateur pianist and vocalist who performed at local concerts, both as a soloist and accompanying other singers. She also played the organ for services at the local Presbyterian and Anglican churches. Ross followed in her footsteps when he was quite young, and Lyall took up the button accordion, playing his first gig at the age of eleven when the musicians booked for a school dance failed to turn up. He and Ross became well known all over the district for providing the music at old-time dances, and when the war started they were part of a concert party that travelled across the region raising money for the Red Cross.

Well before the days of television, and even after it, sitting down in the evening with family and friends to play music was a favourite pastime for all the family. A few days after Elaine and her brother arrived, the Harfulls entertained their likewise musical friends, the Fletts. A few days after that there was another musical evening, this time with the Chambers family from the farm across the road. Everyone who could played and there was no doubt a pause at some stage for a fine supper of home-baked treats served with plenty of tea.

After ten days, Elaine and John returned to Melbourne. The visit obviously went well because the following Easter, less than a year after they met, Elaine and Lyall became engaged. Before making it official, they travelled to Bendigo so the prospective groom could meet Elaine’s extended family. Her Grandmother Schwennesen approved. ‘I never thought you would have the brains to marry anyone like him,’ she told Elaine, forthrightly.

Lyall and Elaine were married a year later on a showery day in April 1946, in the Presbyterian Church at Elwood. It was close to the bride’s family home and it also happened to be under the jurisdiction of a minister who had recently served the Mount Gambier community. Her sister Reay and friend Ivy were bridesmaids, and her oldest brother, Bruce, was groomsman. Lyall’s best man was his cousin John Thomson, resplendent in his RAAF pilot officer’s uniform after returning safely from service in Europe. Ross played the organ, recording in the daily journal he kept most of his life that ‘everything went very well’. Afterwards everyone gathered at a nearby hall for a simple evening meal of cold meat, savouries, cakes and trifle.

2

LIFE AT MIL LEL

The honeymoon that followed Lyall and Elaine’s wedding might well have been the end of the marriage. It certainly gave Elaine a taste of the adventures she could expect in the future with Lyall, who loved exploring out-of-the-way places on back country roads. For their honeymoon, he decided to take her on a caravanning trip to Gippsland. One overnight stop was the old goldmining town of Walhalla, in a deep valley on the southern edge of the Victorian alps. The road in was narrow, winding and very steep, with precipitous drops. More than a few times Elaine was convinced they would end up at the bottom of one. When they finally pulled in to the virtual ghost town, the few remaining inhabitants turned out to stare in wonder. They were the first people anyone could recall who were brave, or foolish, enough to tow a caravan into Walhalla.

On another night they pulled up in a forest. Lyall climbed out of the car and started looking around. When Elaine asked him why, he told her he was just checking which way the trees might fall if the wind picked up. Startled at this hidden danger, the city girl tried not to feel too nervous about the prospect of being squashed while she lay asleep in her bed, and must have been wondering why they were not staying at a genteel hotel. Then the kerosene stove in their little caravan broke down. The next morning a local timber feller came to the rescue and cooked them a hearty breakfast of steak, eggs and chips.

After a fortnight or so, surprisingly unscathed, the newlyweds headed back to Mil Lel and the start of Elaine’s life as a farmer’s wife. They arrived in time for tea, in the middle of a thunderstorm and heavy rain. Two days later they were officially welcomed by the district at a special social and dance held at the Mil Lel Primary School; there was no hall in those days so the school often served as the community gathering point. During the evening there were supper and speeches, and the young couple were presented with an elegant oak pedestal.

Lyall didn’t have much opportunity to dance with his wife that night, even though the party continued until the small hours, because he was part of the band providing the music. She didn’t mind too much, which is just as well given the pattern repeated itself at many other dances over the years. But that doesn’t mean she didn’t dance; there was always plenty of other willing partners.

During those first few days on the farm, Elaine also survived what was known as a tin-kettling. About forty people showed up on a Tuesday night to observe this nerve-wracking tradition, which was still very much alive in rural communities like Mil Lel in the 1940s. It involved friends and neighbours welcoming newlyweds to the district by showing up at their home and banging together pots, pans and any other metal objects they could lay their hands on.

Officially, the couple had no warning. People would wait until they were nicely settled for the evening, sneak up to the house and then make as much noise as possible. Unofficially, they often had at least some idea it was going to happen so they could make sure there was food and drink on hand to share with the revellers afterwards. Only the year before, during Elaine’s first visit, there had been another tin-kettling in the district which apparently got a little out

of hand. A wagon was overturned, a horse let loose, and a man was spotted dressed up in some of the new wife’s clothes!

Lyall and Elaine’s new home was an old farmhouse, which Lyall inherited from his Uncle Jack when he was only fifteen, along with half of the original family farm. A bachelor who bred horses and was a keen member of the local hunt club, Jack named the property Oakbank Farm, after the home of the famous Great Eastern Steeplechase in the Adelaide Hills. The land was always run as an integral part of his brother William’s share on the other side of the block, but Jack built his own house and moved there after William and Amy married in 1910. He later returned to the home farm to be cared for by them in his old age, and his house was rented out.

Solidly constructed of local limestone, it had a verandah across the front and a central passageway leading from the front door, with two rooms on either side. All the rooms had high ceilings, fireplaces and dark timber architraves and doors, which seemed to suck out the light despite generous sash windows. There was a small porch at the back, and the toilet was in the garden.

In between the oat harvest, threshing grain and their frequent gigs as musicians, the Harfulls worked hard to spruce up the house as much as possible before the wedding. Lyall and Ross bought some chairs, a hall stand and a double bed at an auction. They fixed the kitchen chimney and painted the master bedroom with kalsomine, a lime-based wash that came as a powder and was then mixed with water. Then, while the newlyweds were on their honeymoon, Amy and Ross finished setting it up, buying a new kapok mattress and blankets for the bed.

Lyall and Elaine had been resident for about a fortnight by the time the kitchen was painted and a tap had been installed to provide cold running water. That was the extent of the plumbing in the entire house. There was a bathroom and a laundry on the back porch, but it took almost a year before the pipes for cold water were laid there, too. However, Ross helped Lyall fit out the laundry with a new set of concrete wash troughs, purchased for £3 and 5 shillings, and a copper for washing clothes in hot water. Hot water for the kitchen and bathing was heated in a square copper urn that sat on top of an old Metters wood stove in the kitchen. The urn had handles on either side so it could be carried to the bathroom and emptied into the bath.

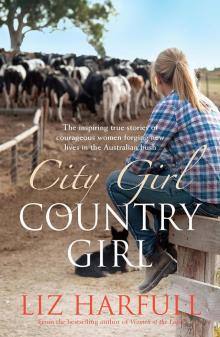

City Girl, Country Girl

City Girl, Country Girl