- Home

- Liz Harfull

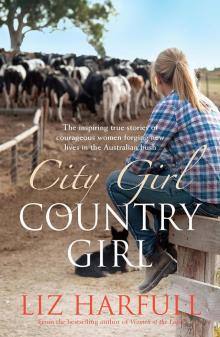

City Girl, Country Girl Page 3

City Girl, Country Girl Read online

Page 3

Mains power was not connected to the farm until 1961. In fact, for the first four years there was no electricity of any sort. Kerosene lamps lit the house, and there was no way to chill food. Elaine and Lyall’s oldest child, Roger, was three and his sister, Valerie, about eighteen months old when the first electric light was fitted in 1950, powered by a 12-volt generator set up across the yard in the dairy. Cables fed the supply to two large batteries stored on the back porch.

Elaine had to wait another two years to get a washing machine; however, Lyall did lash out and buy her an Australian-made Silent Knight refrigerator for the princely sum of £71. The generator only ran for a few hours at night and wasn’t capable of handling too much demand, so the fridge was kerosene powered, but at least it boasted a small deep-freeze section. Elaine celebrated by making ice-cream. In a rush of technological advances, a few months later the house finally got a telephone, which hung on a wall in the hall. It was a shared extension of the phone at Amy and William’s house, but at least it was a phone. People from properties further out, who were not so lucky, would frequently drop in to use it.

These new luxuries were possible because Lyall took the step of setting up his own dairying enterprise. In the first year of marriage, he was given just £5 a month ‘in lieu’ of wages for his work on the farm, but that and his earnings from playing music were not enough to live on and improve the quality of life for his family now that they had two young children. So he built a cowshed about a hundred metres across the yard from the house, and in December 1949 started milking a herd of twenty cows, which was pretty typical for the time. The milk was put into ten-gallon metal cans and carted just across the road to the Mil Lel Cheese Factory.

Well known for producing high-quality mature cheddar, the factory was established in 1889 by John Innes and his remarkable sisters, Janet and Lizzie, to make cheese and butter. The women took over ownership of the business five years later, with Janet acting as manager. According to an obituary in the local newspaper, to hold the position she needed a certificate to operate the factory’s steam boiler. Obtaining a certificate usually involved sitting an examination, however Janet was allowed to side-step this process because of her ‘long experience’, becoming the only woman in South Australia with such a qualification.

The Innes sisters stopped making cheese in the mid 1910s and the small weatherboard building sat idle until they eventually agreed to sell it to Jack Frost in 1925. A talented businessman and cheese-maker, who learnt the craft from his father, Jack walked away from a promising career managing a highly successful factory because he wanted to run his own enterprise. His decision caused an uproar at the time, with many people predicting he would regret it, but Jack turned the business into one of the most successful cheese-making operations in Australia.

After starting with only sixty gallons of milk a day, by the mid 1930s Frost had built a new state-of-the-art facility which was processing 1600 gallons a day, including milk from the Harfull farm. By the time Lyall became a supplier, Mil Lel mature cheddar was being exported overseas and winning major awards, and the factory was making 600 tonnes of cheese a year. In 1951, Jack sold the business to the Kraft Walker Cheese Company Pty Ltd, a major national business best known as the makers of Vegemite. The purchase figure wasn’t disclosed, but weeks before the sale the factory had been passed in at auction after bids went as high as £40,000.

The factory did more than provide an income for the Harfulls. It housed the district post office, and ran a well-stocked general store where Elaine could buy fresh bread and groceries, without having to tackle the rough gravel road into town. It also gave her some close neighbours, helping to reduce the sense of isolation after living in city streets for most of her life. The Frosts lived in an old weatherboard house next to their business, and Jack built two new houses directly opposite Lyall and Elaine for his sons. After they sold the factory to Kraft, the new manager, Gordon Judd, moved in with his wife, Jill, and their six children. They became lifelong friends.

It all added to the vibrant social life of the small community, where there seemed to be a dance every week, and a host of activities centred around the school and various sports clubs, on top of the busy round of private parties and family gatherings. Then there was the annual show to look forward to in October, where Elaine was soon roped in to help on the sweet stall, and the ‘Christmas tree night’ in December which marked the end of the school year, with musical performances, the presentation of school prizes, gifts for all the children and supper. Both traditions are still going strong seventy years on.

But despite the many social opportunities, there is no doubt the first years at Mil Lel were challenging for Elaine. No matter where she was, she felt like part of her was missing. She made at least one extended trip back to Melbourne every year to see her family, although Lyall could often only stay a few days because of his responsibilities on the farm. Sometimes he would drop her off at the bus stop in Mount Gambier, or he might drive as far as Warrnambool or Hamilton and put her on the train. She would cry during the trip at the prospect of being away from him. Then she cried again when she left her parents, because she hated parting from them, too, especially her mother who had been diagnosed with diabetes which was starting to affect her eyesight. She would eventually go completely blind.

Elaine’s family did their best to compensate by frequently coming to stay on the farm. Sometimes they came for extended visits, and on other occasions they took the luxurious option of flying in for the weekend on one of Ansett Airways’ new Douglas DC-3s. After boarding at Essendon aerodrome, they would settle into its blue leather seats and, providing the flight was not too rough, enjoy the novelty of a meal served by an air hostess. The Harfulls would be waiting at the other end to collect them. Not far from the farm, the Mount Gambier aerodrome was the base for a RAAF air observers’ school during the war and had excellent facilities compared with many other country towns.

During those first few years there seemed to be hardly any time at all when the Harfulls were not either on a trip to Melbourne or juggling visitors from the city. If it wasn’t family, including various cousins, uncles and aunts, it was Lyall’s mates from the air force. Elaine’s youngest brother, John, often spent most of the summer on the farm, establishing a pattern that would be repeated by his children and all the other city cousins for the next thirty years or more.

Then came the remarkable day when Elaine discovered a childhood friend from Melbourne was living in the Mount Gambier area, too.

3

FOR THE LOVE OF GRACE

Elaine and Grace Bissett came to know each other in Sunday school. Grace can’t quite remember their age at the time, but they were old enough to have started taking an interest in boys. ‘They used to have a fete at the church every year, and one of the things they did was sell postcards to us kids, and we would write on them and address them to a boy, and someone would deliver it,’ Grace says. ‘Elaine was keen on a boy called Gordon and I was keen on his younger brother. That was one of the last things I talked to Elaine about. I couldn’t remember Gordon’s name, but she remembered it straight away.’

Grace grew up in the Melbourne suburb of Glen Iris where Elaine’s father ran a delicatessen for a short while. After the war started, they would sometimes catch up briefly in the city during their lunch hours. By then Elaine was working at Fred Hesse’s. As soon as she reached the age of eighteen, Grace enlisted in the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Airforce (WAAF). She spent the next three years at the Victoria Barracks on St Kilda Road working as an office clerk, and would often go into the city during her lunch hour. ‘I would sometimes run into Elaine down near the GPO. We were both stressed for time because I had to be at the Barracks and she had to be at work, so we couldn’t talk for long,’ Grace recalls.

Then the two friends lost track of each other. Unbeknown to Elaine, Grace married the son of farmers just a few kilometres up the road from the Harfulls. Ray Gilmore was also in the RAAF. He was

a flying officer and the wireless operator in a Liberator bomber crew when Grace met him. The second pilot, Ron, was going out with one of Grace’s best friends, Bonnie, who kept saying to her, ‘You must meet Ray. I think you’d like him.’

Bonnie and Ron were engaged before Grace finally met the mysterious Ray. When she first spotted him standing in the doorway of a shop with Ron, waiting for the girls to hop off a tram, she wasn’t impressed. ‘He was an officer, and I had no time for officers. I was only a corporal and they used to take it out on you.’

Turning to Bonnie, she said, ‘You never told me he was an officer.’

‘Well, it’s too late now, he’s seen you,’ her friend replied.

The party of four headed off for dinner together, and that was that. Grace and Ray announced their engagement in March 1945 and married two months later, while the rest of Melbourne was celebrating Victory in Europe Day, following Germany’s unconditional surrender.

It was the following year before Grace and Ray were both discharged from the services and headed for Mount Gambier. They moved to Kongorong, south-west of the town, where relatives of Ray’s managed the store. They were meant to be moving into a small farmhouse, but the tenants in residence had refused to move out. ‘So we lived in one room in the store,’ Grace says. ‘Uncle Alb offered Ray five dollars a week and keep if he would work for him and drive his truck up to the Mount every day.’

Meanwhile, Ray’s parents built a new house on their farm at Attamurra, a few kilometres north-east of the town and only about six kilometres from the Harfulls. When it was finished enough to be habitable, they offered their son the old home—a small cottage made of corrugated iron. ‘The kitchen was the dining room, too. Then there was the lounge, and off that was our bedroom, which was a fairly big room, and the other room was the boys’ bedroom. There was a lean-to verandah out the back and a wash house, with a copper in it. I think it even had a dirt floor. I had two big galvanised tubs that were my wash troughs. The toilet was down the yard. The house was on top of the hill and you had to go well down the hill to get to it.’

There was no plumbing or electricity at all in the house. Water was carried in from a tank outside, and the dishes were washed in big bowl on the kitchen table. On bath night, a portable tub was set up on the kitchen floor and filled with water heated in the wash-house copper. Lighting came from kerosene lamps until Ray bought a small engine and set it up in a nearby shed to produce 12-volt power. ‘When you heard it going putt putt putt, everyone made for bed because it was running out of fuel and the lights were about to go out.’

Grace was living at Attamurra when, according to Elaine, they bumped into each other in the main street of Mount Gambier. Seventy years on, Grace struggles to recall the details, but she remembers that Elaine was pregnant at the time with her first child, Roger, who was born in August 1947. Her own first child, Trevor, born in December 1946, was only a few months old.

Once the women reconnected, the two families spent a great deal of time together. By then, Ray had bought his younger brother’s truck and was earning a living by collecting milk from farms seven days a week, and delivering it to cheese factories at Yahl and OB Flat as well as Mil Lel. In those days, most districts had their own dairy factories so milk didn’t have to be carted far, given it was stored in tin-plated cans and there was no refrigeration. Ray would finish his rounds and then, quite often, he would go and help Lyall with the milking.

While the two men worked in the dairy, Elaine and Grace caught up at the house. After they had been fed, the children were put to bed. By then the Gilmores had three sons, who were tucked into the Harfulls’ double bed so the adults could enjoy their own meal without interruption. Then the Gilmores would return the favour, with the Harfulls going to their place. Sometimes they would play cards but mostly they just shared meals and talked. The evenings would never end too late, because everyone had to be up early in the morning.

These informal gatherings became far less frequent in the late 1950s when the Gilmores were awarded a soldier-settler’s block about forty kilometres away at Eight Mile Creek. Situated on the coast near Port MacDonnell, the Eight Mile Creek Soldier Settlement Area covered thousands of hectares of mostly peat swampland. Urged on by the local council, the state government believed it was possible to turn what was essentially ‘hopeless’ ground covered with impenetrable ti-tree scrub into rich pasture country.

Apart from the scrub, there was another major obstacle—water, and lots of it. Much of the area was inundated most of the year, if not permanently. Prospects lifted in the late 1930s when the regional drainage authority set to work building a network of drains to carry the water out to sea. Inspecting progress in 1947, the South Australian Minister of Lands described it as a revolutionary program, and ‘the greatest reclamation and land development work of its kind yet undertaken in Australia’. By 1949 the main drains were in place and an estimated 450 million litres of water was flowing through them every day. It wasn’t enough. The land was still very wet in winter and spring, and not easy to coax into production, especially for servicemen with limited farming experience.

One of thirty-two blocks created with the modest ambition of carrying sixty cows each, the Gilmores’ farm became available because its original occupier couldn’t make a go of it. Even for Ray, coming from a farming family, it was challenging, despite claims by the government that there was no problem that ‘hard work and less complaints’ wouldn’t overcome. Grace remembers struggling to find clumps of dry ground to stand on while they were feeding hay out to the cows in winter. The water lying in the paddock was so deep it ran over the top of her rubber boots.

Clearing the land and keeping it free of cutting grass proved a nightmare. Even with caterpillar tracks instead of wheels, tractors frequently became bogged and local roads were often impassable. In winter and spring, a tractor had to be used to drag the school bus to its destination. A 1953 newspaper carried reports that the children were being jolted so badly during this exercise that it ‘affected them physically and mentally’. Normal methods to improve roads were clearly not working, so it was time for ‘extraordinary measures’, the school insisted.

On the plus side, the new inhabitants at Eight Mile Creek moved onto properties with brand new stone houses, unlike soldier-settlers further west around Allendale and Mount Schank who initially had to make do with RAAF huts relocated from the Mount Gambier aerodrome. However, none of the settlers had access to mains power. Grace had a twelve-volt washing machine which was powered by their car. ‘I had to start the car to run it,’ she says. Eventually Ray installed a 32-volt generator in the dairy, which they hooked up to the house, and things improved considerably.

Very much hands-on with the milking and caring for the herd, Grace spent most of her time outdoors working alongside Ray because their children, Trevor, Norman and Byron, were all at school. Things changed when the twins, Sharon and Lincoln, arrived in 1959, but Grace was still responsible for the farm books and would work outside whenever she could.

Despite the rain and the howling southerly gales blowing straight from Antarctica across a flat landscape devoid of trees, Grace loved the life. ‘It was hard work, but it never worried me because when I was growing up I always said that I would like to live in the country. In those days I imagined a beautiful home and beautiful big trees around me. I don’t think I ever imagined a dairy farm or anything like that, but I adjusted quite well. I enjoyed it. The only thing I didn’t like was leaving my mother, who was alone. That was the only thing I regretted.’

That situation resolved itself in 1964 when Mrs Bissett came to live with her daughter, who cared for her until she died in 1969. In later years, Grace and Ray were in the rare position for many farmers of being able to consider early retirement. Then eleven days after his sixtieth birthday, Ray had a massive stroke. Grace cared for him at home, too, and gradually over the next five years his speech and mobility improved to the point where they were able to do some of the tr

avelling they had planned.

4

TILL DEATH US DO PART

Elaine never spent as much time in a dairy as Grace. In the first few years of married life, Lyall was milking the family herd alongside his brother, Ross, up at the home farm and her help wasn’t needed. By the time Lyall set up on his own, Elaine had two young children to care for, so she concentrated on transforming the old farmhouse and applying the lessons learnt at the Bendigo Girls’ School.

Like so many women in the 1950s, she felt enormous pressure to be the perfect wife and mother, living up to the images depicted in women’s magazines of the day. The house had to be tidy and spotlessly clean. Tasty meals must be ready to go onto the table as soon as Lyall came inside from working out on the farm. An excellent seamstress, she spent hours smocking babies’ clothes and sewing, making outfits for herself and all her children. She turned out everything from coats to ballgowns, including copying a black velvet dress by iconic London designer Mary Quant, right down to its crocheted white collar.

Determined to create a bright, modern home, Elaine oversaw the construction of a new bathroom, and a combined dining room and lounge, separated by a bench from the kitchen. She did most of the decorating on her own, including plastering the very high ceilings in the original part of the house. To reach them, she placed a chair on a table, and then a stool on top of the chair. Lyall came home one day to find her unconscious on the floor after falling from this precarious platform, the plaster dry in her hands.

City Girl, Country Girl

City Girl, Country Girl